Shakespeare himself was a poet, and a playwright––which means that many of the lines in his plays are poems themselves. This style of writing, with the words following a metrical rhythm, is called verse. Shakespeare wrote his plays mostly in blank verse, using iambic pentameter without rhyme. The verse holds many clues to the meaning and emotion behind Shakespeare's lines, so it's important to understand and unpack the verse, in all of its complexity.

Shakespeare himself was a poet, and a playwright––which means that many of the lines in his plays are poems themselves. This style of writing, with the words following a metrical rhythm, is called verse. Shakespeare wrote his plays mostly in blank verse, using iambic pentameter without rhyme. The verse holds many clues to the meaning and emotion behind Shakespeare's lines, so it's important to understand and unpack the verse, in all of its complexity.

Note: Many italicized words in this post are linked to the Poetry Foundation's definition of those terms, as a more extensive glossary. This post includes extensive examples, with links to standard pronunciation provided at least once for every new type of foot.

Iambic Pentameter

The rhythm of many of Shakespeare's lines is in a verse form called iambic pentameter. Iambic pentameter is made up of five (as the prefix "penta-" suggests) iambs. An iamb is a metrical unit of poetry, or foot, composed of two syllables: the first unstressed, and the second stressed. This meter mimics the human heartbeat: ba DUM ba DUM ba DUM ba DUM ba DUM.

To hear the rhythm of the iamb, try reading these five words aloud. Practice emphasizing the underlined portions.

- destroy

- myself

- belong (pronunciation by Merriam-Webster here)

- tonight

- become

Because there are 5 iambs in a standard verse line, standard Shakespearean verse lines have 10 syllables. Sometimes, Shakespeare uses elision, omitting unstressed syllables and replacing them with an apostrophe to decrease the number of syllables in a word, to make certain words fit the meter. Examples of elision include "o'er" (1 syllable instead of 2), "e'en" (1 syllable instead of 2), and "i' th'" (1 syllable instead of 2).

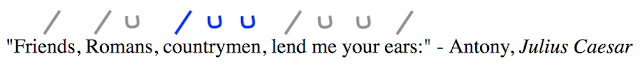

The unstressed syllables are marked with a ᵕ above the line, while the stressed syllables are marked with a / above the line. So, each iamb is marked ᵕ /. Marking all the syllables in a line as stressed or unstressed is called scanning the text (noun: scansion).

Shakespearean Example:

Variations in Meter

However, Shakespeare does not always write in perfect iambic pentameter, just as people do not always speak in the exact same rhythm. Changes to the metrical pattern of iambic pentameter are called variations.

The most common metrical variation in Shakespeare is trochaic inversion. A trochee is a metrical foot composed of two syllables: the first stressed, the second unstressed. The trochee is the inverse of the iamb––hence the name trochaic inversion––because the trochee, / ᵕ, is essentially a backwards iamb.

To hear the rhythm of the trochee, try reading these five words aloud. Practice emphasizing the underlined portions.

- instant (pronunciation by Merriam-Webster here)

- meter

- frightened

- morning

- quiet

Another common metrical variation in Shakespeare is the inclusion of a spondee. A spondee is a metrical foot composed of two stressed syllables, marked / /.

To hear the rhythm of the spondee, try reading these five words aloud. Practice emphasizing the underline portions, leaving a small space between the two stressed syllables at first.

- door bell

- tooth paste

- rain bow

- cell phone (pronunciation by Merriam-Webster here)

- shoe lace

Some other metrical variations––though these are fairly rare––include the dactyl, anapest, and pyrrhic.

The dactyl is a metrical foot composed of a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables. Thus, the dactyl is marked / ᵕ ᵕ. Examples of the dactyl include "elephant," "fabulous," and "daffodil."

Shakespearean Example (the dactyl is marked in blue):

Notice the trochaic inversion of "lend me"?

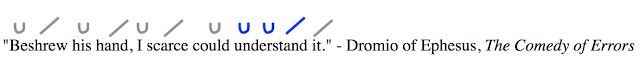

The anapest is a metrical foot composed of two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable. Thus, the anapest is marked ᵕ ᵕ /. Examples of the anapest include: "overcome," "contradict," and "understand."

Shakespearean Example (the anapest is marked in blue):

The pyrrhic is a metrical foot composed of two unstressed syllables, marked ᵕ ᵕ. Pyrrhics are very rare, so there are not many English words that are pyrrhics on their own. Examples of pyrrhics include the phrases: "of a," and "of the," when followed by a noun.

Shakespearean Example (the pyrrhic is marked in blue):

So how do you know if a line is written in straight iambic pentameter or with variations?

Meter is somewhat subjective to the reading of the actor. Try reading the line out loud to see where your voice naturally stresses the words in the line. Those natural stresses will unlock meaning and emotion behind Shakespeare's words and phrases. You could also look online for some videoed readings of that line to see the scansion that other actors used.

Interpreting Meter

Noticing these metrical aspects of Shakespeare is wonderful, but it is critical that you interpret the things you have observed. Interpretations vary a great deal among scholars, as you can imagine, but here are some basic and versatile suggestions that can jumpstart your interpretations when the blank verse is not standard, as you expected.

There are more than ten syllables in a verse line

An extra syllable in a line means that the line has a feminine ending. Feminine endings could mean that a character has not finished formulating their ideas yet, and are still speaking to clarify those ideas (Shakespearean Example 1). Feminine endings might also indicate that the character is experiencing intense emotion, like excitement or distress, that causes him/her to speak differently than the norm (Shakespearean Example 2).

Shakespearean Example 1: Contemplation (the extra foot is marked in blue)

Shakespearean Example 2: Intense Emotion (the extra foot is marked in blue)

There are less than ten syllables in a verse line

Quite simply, a verse line with missing feet means that there is some other action to fill up the last few beats of the line. That action could be a moment for a character to think or reflect (Shakespearean Example 1), or the time needed to carry out a physical action needed in the scene (Shakespearean Example 2).

Shakespearean Example 1: Moment to Think (the missing feet are marked in blue)

Shakespearean Example 2: Physical Action (the missing feet are marked in blue)

Two lines rhyme with one another

Two lines whose end words rhyme with one another are referred to, together, as a

rhyming couplet. Shakespeare often places the rhyming couplets at the end of a scene to signal that the scene is coming to a close (Shakespearean Example 1). In other cases, rhyming couplets are usually associated with love (Shakespearean Example 2).

Shakespearean Example 1: Ending of a Scene (the rhyme is marked in bold)

"The time is out of joint. O cursed spite!

That ever I was born to set it right!"

- Hamlet, Hamlet

Shakespearean Example 2: Love (the rhyme is marked in bold)

"Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind;

And therefore is winged Cupid painted blind."

- Helena, A Midsummer Night's Dream

Two lines make up ten syllables of regular blank verse together

When two lines make up ten syllables, together, the second line is indented after the first, as in the example below. This means that there is very little space between the lines––the characters are often interrupting each other, or picking up on each others thoughts and responding quickly.

Shakesperean Example:

The line is not in verse at all

When part of the text of one of Shakespeare's plays is formatted like a regular paragraph and has no structured meter, that text is said to be written in prose. In that case, you do not scan the text.

Prose can be used for casual conversations, and conversations not too deeply tied into emotion. Prose is also often used between lower status characters––most conversations in which there is a status difference in the characters or in which the characters are high status are written in verse. Prose can also be thought of as the character's most unfiltered and even unorganized thoughts, so prose is often used for drunk characters. Read our post on Shakespeare's use of prose here.

Shakesperean Example:

"Come sir, you peevishly threw it to her: and her will is, it should be so returned: if it be worth stooping for, there it lies, in your eye; if not, be it his that finds it."

- Malvolio, Twelfth Night

Comments

Post a Comment

All comments are moderated by the Green-Eyed Blogger to avoid spam. If you do not see your comment right away, do not worry; it is simply undergoing our routine moderation process.